Molly Segal

What We Whispered and What We Screamed

July 8 - August 5, 2023

for inquiries email sean@track16.com

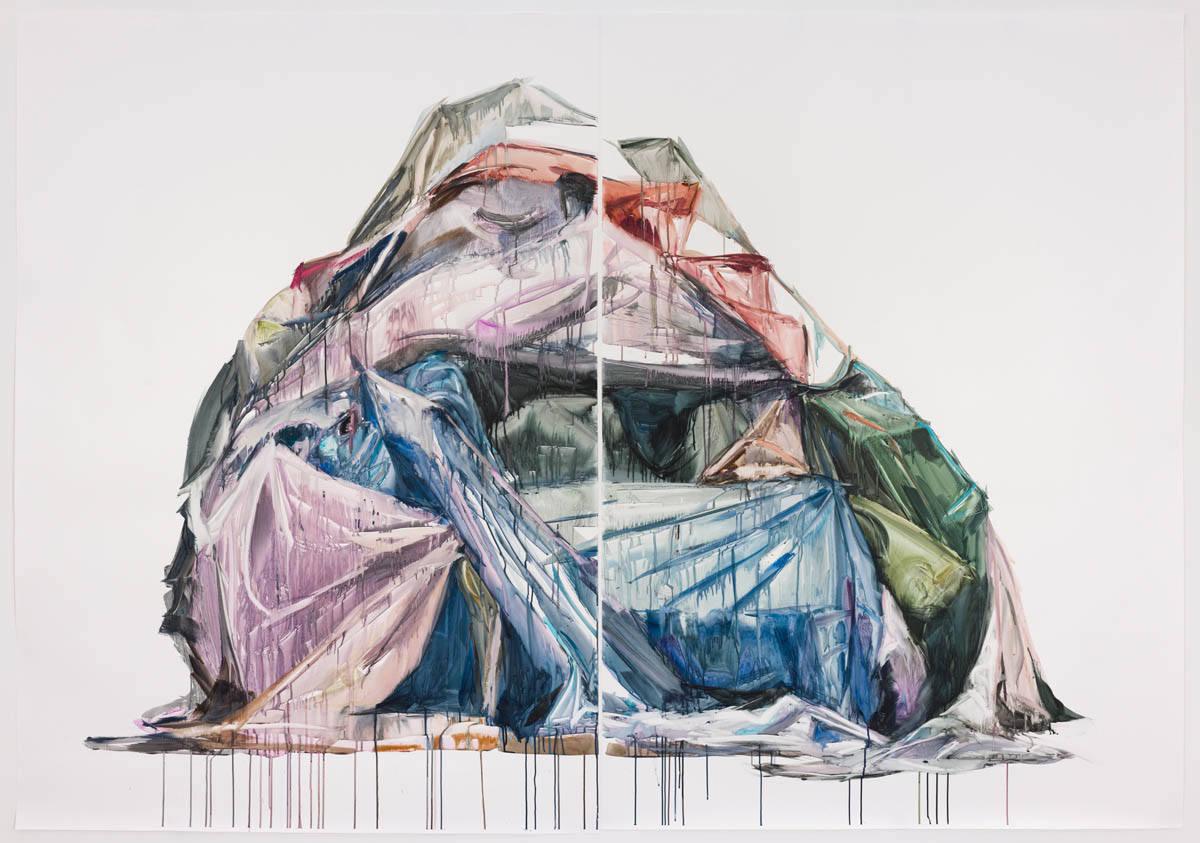

Wildfires, orgies, tent cities, and whale carcasses are just some of the recurring imagery in this newest body of work by Molly Segal. On display are a series of watercolor paintings ranging in scale from intimate to epic size.

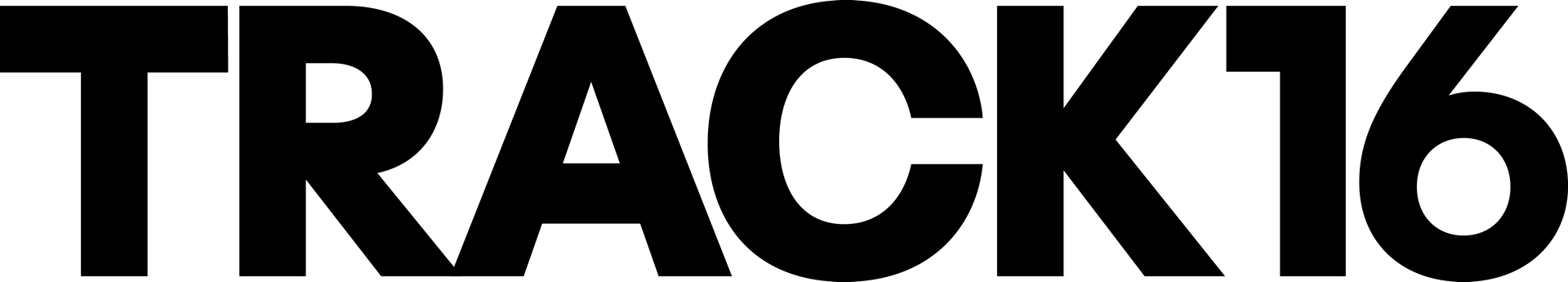

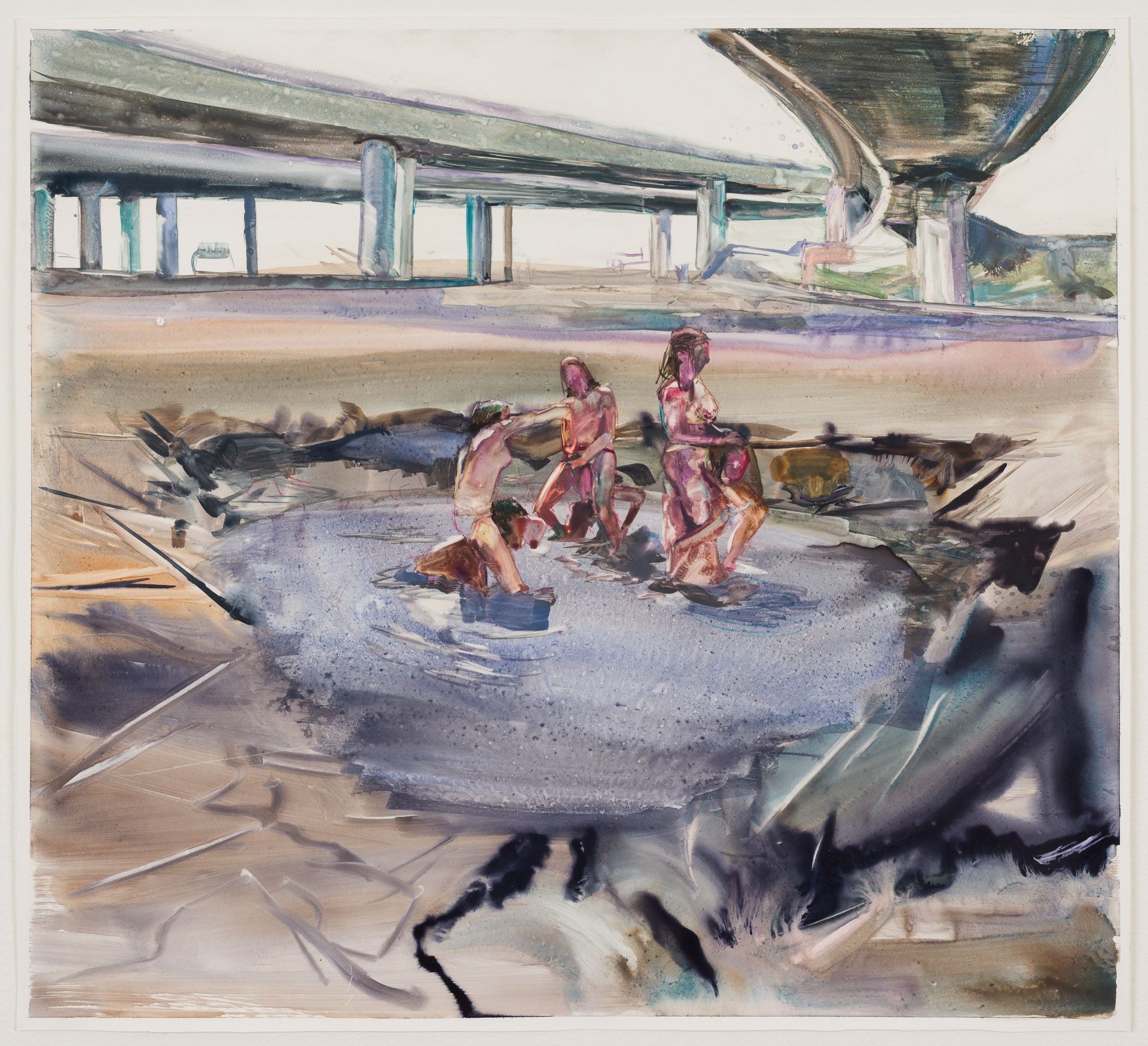

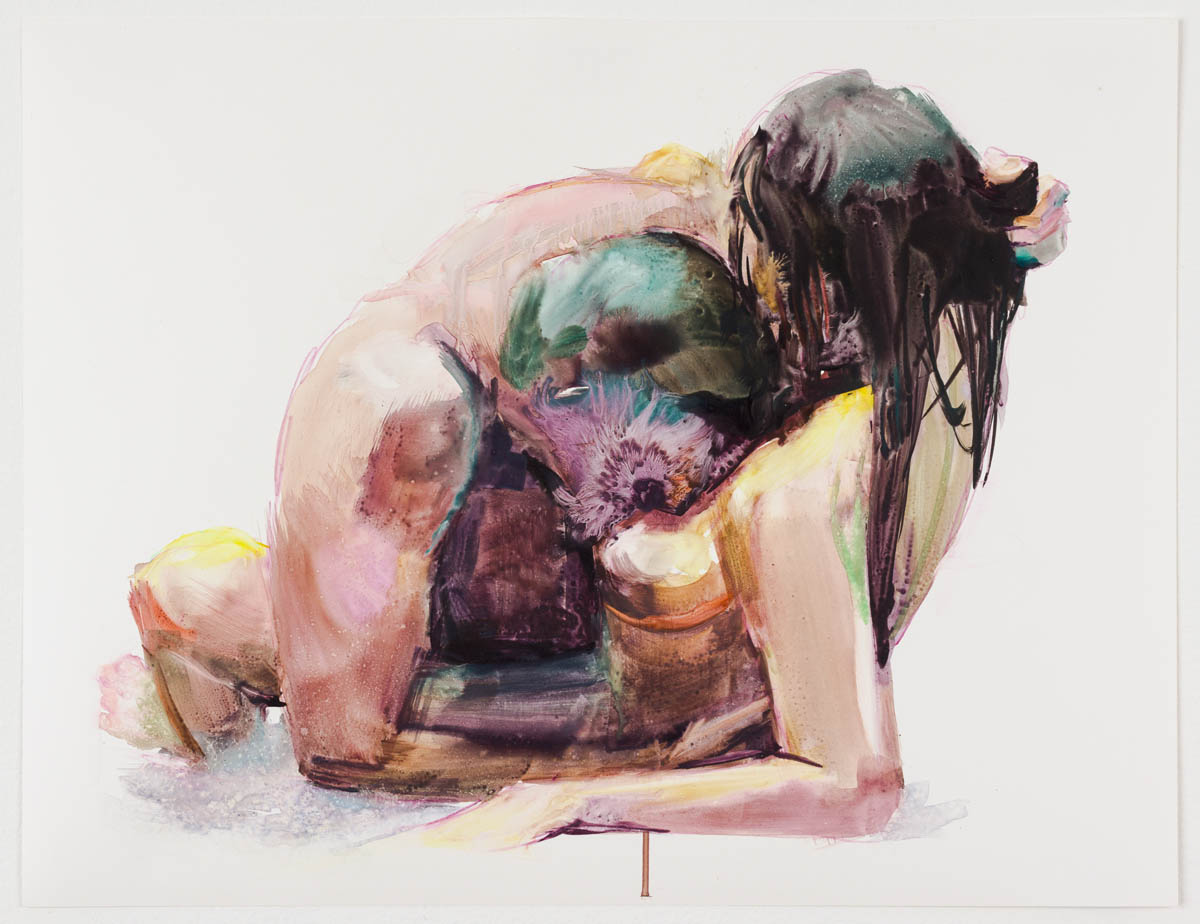

Cycles and opposition fascinates the artist: the undercurrent of living and dying, pleasure and destruction, all in coexistence. Delicate, luminous scenes in muted hues depict freeways, empty construction sites, and hills ablaze with wildfire, at times choking the scene with gray smoke. At the same time, playful figures engage in sexually pleasurable activities–seemingly unaware of the barren landscapes they inhabit. They seem blissfully absorbed in their activities and unbothered by the destruction surrounding them.

Figures are often hidden or secondary. In one piece, an exposed whale carcass hides gestural figures in the midst of an orgy, their forms blending into the exposed innards of the rotting whale. Whales continue as a motif, lying among a towering pile of scrap metal or at the base of a circle jerk. Unlikely elements are juxtaposed within the environment, yet human activity affects it all. Tents recur as well; solitary tents sit against a ground of unpainted paper in loneliness and isolation–a landscape familiar to every viewer.

Segal uses a plastic paper as her surface. This technique allows the paint to sit on top of the paper and move freely, allowing a surface both impermanent and exposed during the process. The pigment becomes bolder and more saturated, while leaving the painting itself more vulnerable to the elements.

I Am Still Right Here [detail], 2023

Watercolor, gouache, and salt on paper.

60 x 196 inches

more info

The artist’s work is a quietly confrontational lens into the time we exist in. As she mentions, “we are the richest place on earth at the end of the world.” The environment holds finite resources and, in one sense, the human population is complicit in the destruction. The work is not overly didactic; Segal finds humor in the bleakness, “we're all watching a disaster and jerking off.”

Molly Segal is a Los Angeles-based painter. Born and raised in Oakland, Segal is interested in her home state of California as a site where disaster and decadence converge. Her large scale watercolors explore fragile connections, finite resources, and the price of survival in inhospitable climates. Her paintings have been exhibited at Charlie James Gallery, The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Zevitas Marcus Gallery. She was an inaugural artist-in-residence at the Quinn Emanuel Artist Residency in Los Angeles in 2021. Her work has been featured in the New York Times, Whitehot Magazine, Artillery, and Lapham’s Quarterly. She received her MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in 2013.

Dry Mouth, 2020

Along Rivers and Valleys, 2023

Fire Study, 2022

Home Was A Dream, 2021

Gobble Me Swallow Me, 2023

I'm Gonna Make Noise When I Go Down, 2023

Give Me Everything You've Got, 2023

There Is No End To What A Living World Will Demand of You, 2023

Laugh Until We Choke, 2023

I Am Truly Sorry About All This, 2023

We'll Go On Like We've Always Done, 2023

The Old Familiar Sting, 2022

When Smoke Changes The Color Of The Sun, 2023

Make It Rain, 2022

I Am Still Right Here, 2023

Hand In Unlovable Hand, 2023

Forever, This Time, 2023

Leave Your Boots By The Door, 2023

Slowly First Then All At Once, 2023

WORKS IN THE EXHIBITION

INSTALLATION VIEWS

Do the materials change or guide your process?

Materials definitely guide the process. I usually start with a rough sense of what a painting might turn into, but as the painting progresses, my job becomes interpreting and responding to what the paint is already doing on its own. So it ends up feeling like a real collaboration between my ideas and what the paint wants to do. I really feel that NO other media will work as hard for you as water media does. It moves on its own. It dries and stains differently. Different pigments and types of paint interact in specific and unique ways with water and each other. So my job is often that of conductor; understanding and directing the chaos of what the paint wants to do.

What are some concepts that you think about in making your work?

I grew up in Northern California and I live in Southern California now. And California is just a state where disaster and decadence are right next to each other. In like, an intimate way. Our fire seasons are getting longer, our droughts more severe, our wealth disparities more pronounced. So I think a lot of my work is about finite resources and the cognitive dissonance it takes to exist here in 2023.

When I did an artist residency at Quinn Emanuel law firm recently, it felt like two things were growing exponentially in DTLA: construction sites and tent cities. And it felt like they were on a graph that would never cross. These things are deeply, intimately related and yet feel impossibly far apart.

Who and what gets to survive in a place like this?

Can you talk a little about the aspect of sexuality and orgies in your work?

Some overarching themes or drivers in my work are exploring finite resources and the costs and limits of intimacy. And I guess the sex serves as a stand-in for that for me? Something about the disintegration of the self, of the body–and the many ways that pleasure and destruction can exist on the same plane. Moments of intimate connection sometimes strengthen us, they sometimes leave us vulnerable. They often just distract us. There’s something beautiful and terrifying about all of our fragile little connections in the face of so much chaos.

What is your artmaking process like in the studio?

It’s so important for me to leave room in my studio practice to make bad paintings. Dumb paintings! Failed paintings! Embarrassing paintings! Corny paintings! I think for a long time I would self censor my work, not make something unless it felt fleshed out and meaningful. One time I was telling my professor Gerry Bergstein I wanted to make a painting but I was pretty sure it was an awful idea and he grinned at me conspiratorially and said, “Well you don’t have to show anyone.” And it fucking rocked my world. So now it’s really important for me that I edit my ideas out in the world, and not in my brain, if that makes sense. And that’s led to better work for me.

I also think the “make bad paintings” thing allows me to paint more freely and not get too precious. I paint best when I’m not attached to the painting. That’s when I get brave. So there’s always an elaborate scenario in the studio where I’m convincing myself that none of this matters, that none of this means anything. That’s also probably why I work on paper. It’s just a piece of paper! Who cares!

What is your opinion of the intersection of social media and the art world? How does your work translate online?

I actually think my work translates relatively well online, but with newer work, like what’s in the exhibition, I think there’s a real atmospheric quality and a lot of texture and details that are really best experienced in person.

People will often say, “Oh, my God! I had no idea these were this big!” or “They’re so different in person.” And I choose to take that as a compliment because at the end of the day I make objects, and if it doesn’t feel any different to stand in front of my object than looking at it through a little screen, then I might be out of a job.

But also a lot of those people who are standing in front of my paintings found me through social media. So I feel grateful that the internet gets people in the doors and I hope that the physical work offers a new and deepened experience.

Instagram especially has been a very useful tool for me and my career, in terms of networking, finding new artists, communicating with peers and galleries, and cataloging what I see.

How was your experience in an MFA program? How did it help you develop the work?

I think there are so many supremely correct and righteous critiques of MFA programs, but I can’t deny my time in grad school was pretty transformational. My work and perspective went through a major shift. Materially it became much looser and conceptually it became much further in line with who I am and how I think. Grad school also coincided with my first time living away from my hometown at the age of 27, so I’m sure that was part of it in terms of allowing me space to help contextualize a lot of my life. I attended The Museum School in Boston, a school known for performance art and highly conceptual ideas. And that was just perfect for me, someone with a fair amount of skill, who needed to be stretched and challenged conceptually. More than anything, the most important thing I left grad school was a group of cohorts, particularly a small group of other artists who I still heavily lean on for critique and inspiration. We are still in a very loose collective called FIG. It’s made up of myself, Coe Lapossy, Courtney McLellan and Annie Blazejack. They’re all brilliant and brilliant artists.

Do you have a certain message that you want to convey?

I think in my work, and in my life, I have a kind of constant itch to ask everyone around me, “We're all seeing this right?” We're all witnessing the same thing right? We're just going to watch it burn?

I can’t tell if it’s that I’m hyper-aware of what’s around me, or if it’s just that I’m unwilling to look away? I’m definitely sensitive to rhythms and cycles of a million little deaths and regenerations I see every day. Whether it’s a dead pigeon, a neighbor living on the street, or a building being torn down. To an extent I see myself as a witness, a cataloguer, an antennae, but I don’t see my work as prescriptive. I don’t have many answers that I think can be solved through art.

I have really loved some interpretations viewers bring to the work. There’s obvious political or environmental aspects of the paintings, but I’m really tickled when people respond emotionally, or viscerally. One stranger told me the work made her think about the ways she’s used sex to feel tethered to the earth during tumultuous times. An oil executive once looked at one of paintings and said and “Well, in my line of work you’re either fucking or being fucked.”